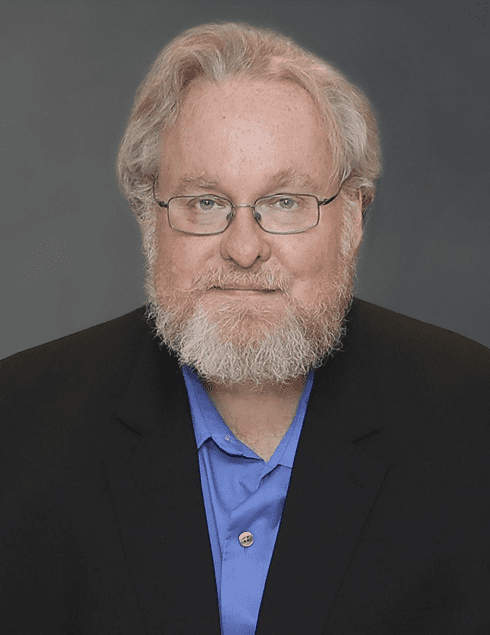

Here we have it. Finding Poland’s first guest post, written by polka music radio show host and author, David J. Jackson.

Following on from Finding Poland’s review of David’s book, Classrooms and Barrooms: An American in Poland, David kindly agreed to write a guest post on a topic of his choice. He decided to share his reflections on the similarities and differences between Polish culture and Polish American culture. A polka radio show host himself since 1998, David also explains how polka music helps Polish Americans to connect with their ethnic heritage.

Strap yourself in for an eye-opening ride …

By David J. Jackson:

I consider myself Polish American. My Polish ancestors came to the US more than 100 years ago. Their journeys included working in heavy industry when there weren’t any of the worker protections of today, supporting their unions, owning their own businesses, and always wanting something better for their kids. I am proud to be Polish American.

I am not Polish. I was not born in Poland and I speak the Polish language poorly. There is a difference between Polish and Polish American. Even if the language we use to describe ourselves sometimes makes it seem like we don’t, Polish Americans know the difference.

Polish American culture

Polish culture and Polish American culture are related, but not the same. The closer we are to when we or our ancestors arrived in the US from Poland, the more likely our Polish American culture is to resemble Polish culture. We Polish Americans whose ancestors came to the US in the great wave of immigration at the turn of the 19th to the 20th century are quite far removed from Poland, and the Poland from which we are removed bears little resemblance to the Poland of today. Yet we still feel a connection to Poland. We derive meaning from our identity, even if it is expressed primarily symbolically, at events like Polish festivals, Dyngus Day parties, and Pączki Day.

Polka music provides Polish Americans of our cohort, the third, fourth and fifth generations removed from Poland, a connection to our ethnic heritage. We know polka music as it exists in North America does not exist in Poland. Sometimes the Polish sung by polka musicians is badly pronounced, non-grammatical, and not at all like the contemporary version of the Polish language. This is because much of the Polish sung on polka recordings was learned from previous recordings, and the original singers did not speak contemporary Polish. John Góra, a Polish Canadian polka singer whose Polish is flawless because he was born in Poland has said, “I’m more than happy to help bands with their pronunciation. (Some bands) just do it phonetically but what they heard (initially on some older recordings) was recorded wrong and so it’s going to sound wrong again.”

Polka radio programs provide Polish Americans with a sense of community. I have hosted four different polka broadcasts on and off since 1998, most recently hosting the Sunday Morning Polka Show of Northwest Ohio since 2011.

Polka radio helps create and maintain the Polish American community. When I did my radio shows in Detroit and Saginaw, Michigan, in the late 1990s, we would receive dozens of phone calls during each episode requesting dedications of songs for birthdays, wedding anniversaries and other special occasions. Listeners mark these milestones by sending out a song to each other, frequently “Sto Lat” or some version of the “Anniversary Waltz.” I like Gene Wisniewski’s version of that song best, because it’s in polka tempo. Polish Americans share important family events through a polka radio broadcast because they want the Polish American community to know about the milestone, and to celebrate it with them.

How the Polish language defines Polish Americans and helps them to bond

Even if the Polish language on some polka recordings is imperfect (and some of it is in fact quite good), people feel a connection with their ancestry when they hear the language sung, even if they cannot speak it themselves. For most Polish Americans of the third, fourth and fifth generations and beyond, the Polish language has lost its daily usefulness. We do not need to speak it in stores, or in church, or to our grandparents or parents. However, Polish Americans want the language to remain in their lives.

Scholars have suggested that just the idea of the Polish language is something that defines some ethnic Americans, even if they cannot speak the language fluently. We greet each other with a hearty “Jak się masz?,” and thank the butcher at the local Polish American meat market with “dziękuje.” We make silly jokes using the language, such as, “Dzień dobry, dziękuje, Gene Autry,” or instead of saying “Na Zdrowie,” we sometimes say, “Nice Driveway.” Polka radio provides a way for the language to remain in the lives of Polish Americans, as do polka band performances at Polish festivals. Many of the polka fans who have been faithful listeners to my shows cannot speak the Polish language, but have reported to me that they love hearing it, because it reminds them of their parents or grandparents. That’s real.

On my current polka radio show, I try both to practice my Polish and share the language with the audience. This is done not just through the playing of many songs with Polish language lyrics, but also through the “Polish Word of the Day” feature. Using Transparent’s Polish Word of the Day, I offer a different Polish word each week, and use the word in a sentence. The audience suffers through my pronunciation, but together we enjoy the contemporary Polish language being spoken. As I take a Polish language lesson each week, I also offer what I know of how the word fits in the sentence grammatically, what case it’s in, and whatever else I can manage to remember from the lessons. I don’t want to overdo it, because I know most listeners come to the show to hear the music. But I enjoy this chance to practice pronunciation, and it helps others to learn as well. After all, the old cliché, “see one, do one, teach one,” applies to language learning too!

Polish Americans of the third, fourth and fifth generations and beyond have not only usually lost the Polish language, but we have also often lost a personal connection to Poland, and for similar reasons. Without close connections with relatives in Poland, knowing what’s going on there doesn’t have much practical value. On my current polka show I present a brief news item each week from Radio Poland. It’s usually connected with contemporary politics, Polish contributions to the arts (when it’s a musical contribution, I play some of it), or history. This allows the audience to maintain some connection, and for the large number of Polish Americans who travel to Poland every year, it gives them a little information about what’s going on in the country.

Proud to be a Polish American and a Polka DJ

Polish Americans and the Polish people are distinct but related groups, and different generations of Polish Americans experience their ethnic identity differently from each other. For some Polish Americans, usually those of us of the third, fourth and fifth generations and beyond, polka music is a means by which we experience and express our Polish American ethnic identity. I’m proud to be a Polish American, and I’m proud to be a polka DJ.

Links

* David as host of the Sunday Morning Polka Show of Northwest Ohio – click here for streams

* Reviews of David’s book, Classrooms and Barrooms: An American in Poland – click here

* Grab a copy of Classrooms and Barrooms on Amazon – click here

* Read David’s articles on Medium – click here

OMG! Your article of “Being” Polish really hit home with me. I dont feel so guilty now . Yes!, I’m Polish-American and that’s how I’m going to introduce myself from now on. Thankyou for freeing me. 🤗

Nice article, Dave

I’m third generation Polish , (on my Dad’s side) don’t speak a word but love to dance polkas!

BTW our oldest daughter has visited Poland many times w/ her husband recently.

Joe&Jenny Romp