This interview with Polish Citizenship Specialist, Michał Petrus, on the topic of obtaining Polish citizenship through Jewish ancestry follows on nicely from our recent talk about the range of documents that exist which may prove one’s Polish citizenship through their ancestors.

Michał is a genealogy enthusiast who’s been handling cases connected with confirming Polish citizenship by descent since 2019. He represents Your Roots in Poland, a genealogical and citizenship company based in Kraków.

The interview below is another fascinating read from both a legal and historical perspective. You will enjoy this one.

How does your office view applicants with Jewish ancestors who left Poland during or just after World War I, i.e. before the Act on citizenship of the Polish State of 20 January 1920?

❝ Generally speaking, the emigrations that happened before the 1920 Act are treated the same, regardless of the creed of the ancestor. Basically, Article 4 of the Little Treaty of Versailles stipulated that people with Polish ancestry and domicile in either the Russian, Austrian or German Empires, could apply for Polish citizenship at their respective consulates or authorities in general. This was the same for applicants pursuing Polish citizenship through Jewish ancestry.

With Jewish ancestors, the emigrations tended to happen a little earlier than was the case with other emigrants. Therefore, with economic motivations to emigrate, a lot of those Jewish families left in the early 1920s. This makes our work more difficult because the records that are preserved in the State Archives are mostly from the late 1920s and 1930s.❞

If an applicant’s father or grandfather immigrated to Israel after the Second World War, can you talk about how they would have lost Polish citizenship from a Polish and Israeli legal perspective?

❝ The trickiest part revolves around service in the Israeli military. This is because the Polish Citizenship Act of 1920 defined that one cannot serve in any non-Polish army. The judicial authorities in Poland decreed that the only exceptions to this rule were service in the Allied forces, as well as the Russian Red Army after Operation Barbarossa.

There is no Israeli Army, however, among the list of exceptions. The reasoning behind this is that the foreign army in which the ancestor served had to share a common purpose with the Polish military or the Polish State. Therefore, the various Arab-Israeli wars which broke out from 1948 onwards did not satisfy this demand. The Soviets supported Arab states and not Israel.

This rule about serving in foreign armies came to an end in 1951. The 1951 Act on Polish Citizenship was updated. Serving in the military of another country, apart from Poland, could result in a fine or imprisonment but not the loss of citizenship.

Today’s Polish citizenship specialists have to deal with this very fragile and short period between 1948, when the State of Israel was established, and 1951, when the law on Polish citizenship was updated and military service in another country no longer caused any issues. During this short period, we have to prove that the ancestor that left for British Palestine, and then Israel, didn’t serve in the Israeli Defence Forces. If they did serve in this short period, that would result in loss of citizenship.❞

Can you talk about the all-encompassing nature of conscription in Israel and the other difficulties future generations of Jewish ancestors who moved to Israel before 1950 have faced?

❝ The other sticking point when it comes to one’s confirmation of Polish citizenship through Jewish ancestry is to prove that the ancestor didn’t serve in the Israeli Defence Forces. Not only that, the ancestor must not have been in the reserve force, which was also treated as part of military service in Poland. To prove that, you would need a written statement from the Israeli Defence Forces. I’m sure that many people that have Jewish ancestry in Israel are familiar with the subject.

In the past, the Israeli Defence Forces issued a statement that was both comprehensive and comprehensible for the Polish Government. The declaration stated that the ancestor was not part of the Israeli Defence Forces, or Reserve Forces, up to 1951. However, the Israelis changed the layout and wording of the document. It was a minor change but the Polish Government argued that the document no longer proves that the ancestor was not part of the Reserve Forces either. Hence, one could argue that the ancestor did not serve in the military but they were a part of the Reserve Forces. So we struggle quite a lot with Israeli cases due to this bureaucratic obstacle. Understandably, our clients are generally unwilling to understand why this is the case.

Frankly, I agree that this situation represents an injustice. The cases are not being handled properly and with a human touch I would say. If we don’t want to get a refused application and then go to the Ministry of Internal Affairs with an appeal, and then possibly higher to the Supreme Administrative Court, which would take years to resolve, then I argue that it is possible to get the old template with some flexibility on the part of the Israeli Defence Forces. Unfortunately, I’m not that familiar with the reality of it, in other words pleading directly to the Israeli Defence Forces to issue the old template – but I know it is possible and I’ve seen it done.

With the current situation in the region, the Israel Defence Forces have higher priorities. It has surely become even harder to get this document either in a timely manner or at all.❞

What were the repercussions of the 1951 Act on Citizenship of the Polish State on both Jewish people alive then and indeed future generations of Jewish people, including today’s generation, who believe they have a right to claim Polish citizenship by descent?

❝ As I’ve already alluded to, the 1951 Act did introduce a lot of freedom in terms of citizenship. Ancestors would no longer have lost citizenship if they held public office abroad, served in the military of another country and were naturalised as a foreign citizen. This applied to both men and women.

Frankly, I don’t think the communist regime had such honourable intentions when it came to the 1951 Act on Polish Citizenship. I think that the Government wanted people to keep their Polish citizenship so that they could be held accountable before the Polish Government if they ever returned to Poland. Hence, the act was perhaps introduced with questionable intentions but it does make our lives much easier when it comes to handling cases.

From 1951, it was no longer against the law to hold dual citizenship. The only exceptions were other Soviet states in the area with which Poland signed a convention, namely East Germany, Hungary, the USSR and Czechoslovakia. This limited dual citizenship but Poland and Israel did not have a convention on dual citizenship after 1951. So it was possible to be a Polish and Israeli citizen after 1950 with no repercussions. On the Polish side, at least, one would still be viewed as a Polish citizen.❞

Between 1968–72, around 13,000 Poles with a Jewish family background left Poland because of a state-sponsored “Anti-Zionist Campaign.” What impact did this mass emigration have on claims for confirmation of Polish citizenship among subsequent generations of those who fled?

❝ One thing that comes up for descendants of ancestors who emigrated later is whether these ancestors were forced to renounce Polish citizenship upon leaving Poland. It did happen as there were a few periods in which the communist government persecuted and forced many Jewish people of Polish descent to leave the country.

Fortunately, somebody on the judicial level after 1989 decided that this huge injustice cannot go hand in hand with “Free Poland”. Therefore, all those forced renunciations of citizenship were essentially ignored by post-communist governments. Even if the paperwork states that your ancestor renounced Polish citizenship upon leaving the country, it is understood that it was done unwillingly and under pressure.

So, it is possible to apply for Polish citizenship through Jewish ancestry, even if your ancestor left in 1968 when there was a huge wave of emigration to Israel. Many famous Polish-Jewish people left Poland then, for example, the actor and film director, Aleksander Ford.❞

In terms of the impact on applicants for Polish citizenship through Jewish ancestry, can you talk about cases whereby ancestors’ changed their surnames as a result of emigrating to countries like the USA during various waves of emigration in the twentieth century? Is it usually difficult for applicants to prove by all possible means that their ancestor is the same person?

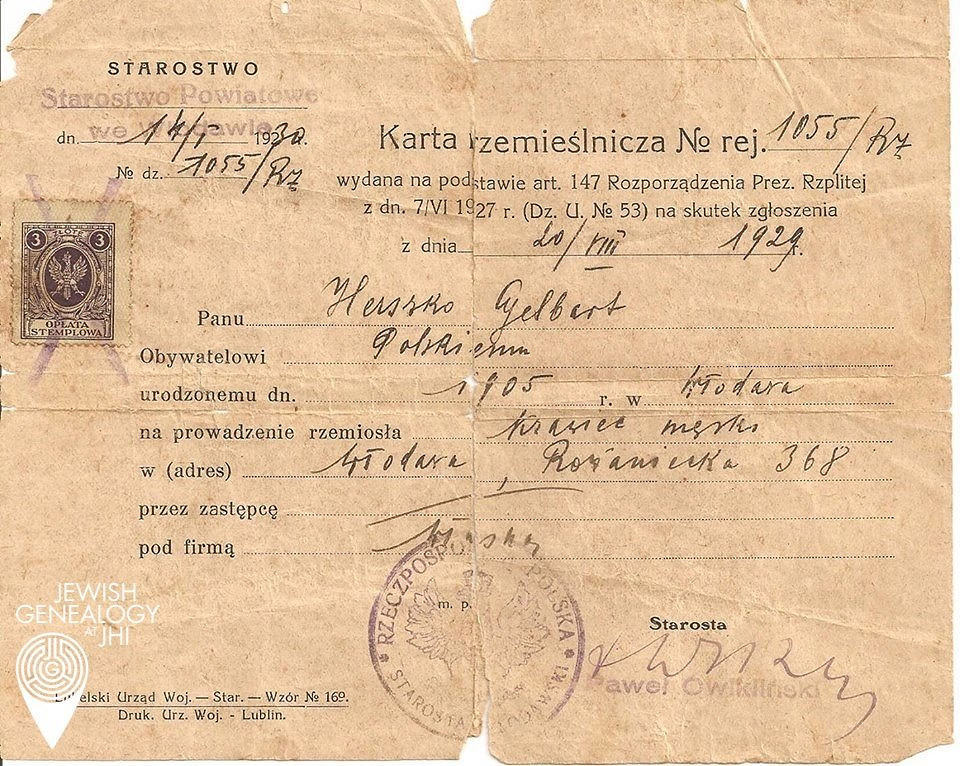

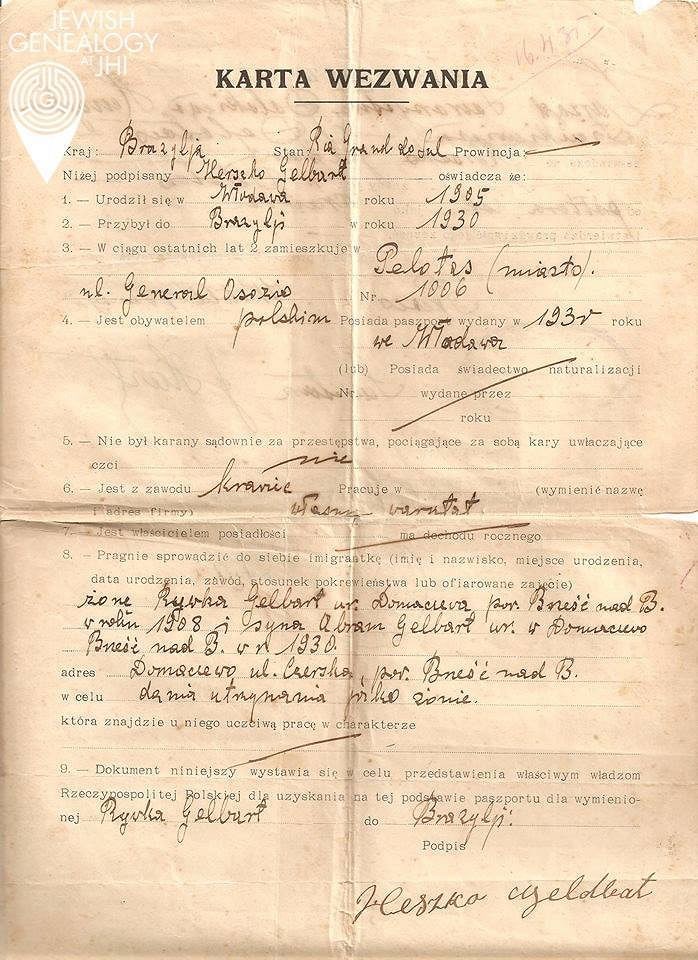

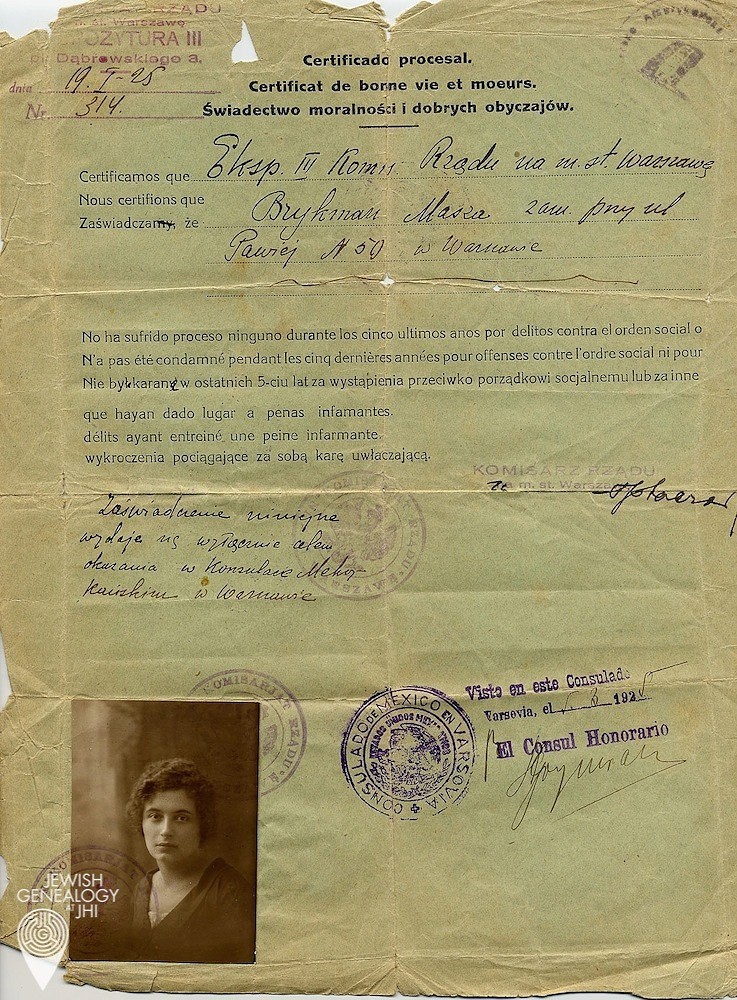

❝ In theory, this scenario should not be problematic to overcome because all you need is a deed poll, which is a document confirming a name change. Unfortunately, a lot of name changes occurred on a non-official level, especially in the first half of the twentieth century. Many Jewish families anglicised their forenames and surnames, or adopted other surnames.

When somebody came to the US and applied for US citizenship by naturalisation, they had to declare under what Polish name and surname they came to the country. It might also be the name they had in a displaced persons camp. This document, called the Petition for Naturalisation, would be our link in proving that this is the same person.

One could also query courts of law, public notaries or other attorneys that one could presume that the ancestor may have gone to in their dealings. I know that it’s difficult to guess which lawyer your grandfather used 70 years ago. However, it’s possible in some instances. Perhaps you have the last will and testament from your ancestor and he used the same lawyer for every matter. Therefore, it might be possible to trace a deed poll.❞

Where are Jewish vital records now kept? Do applications for confirmation of Polish citizenship from Jewish people tend to lead you to different archives and museums compared with cases from your non-Jewish clients?

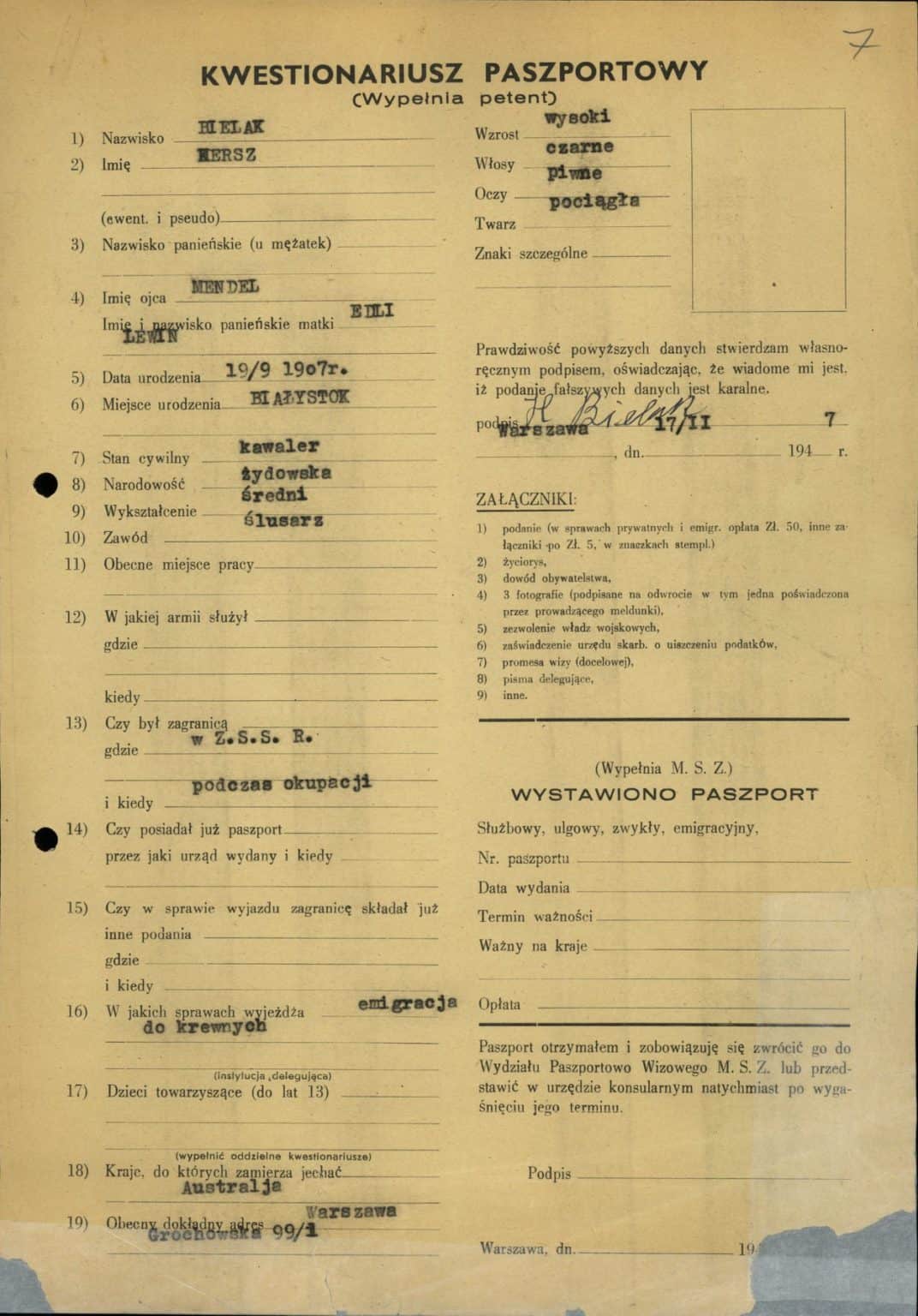

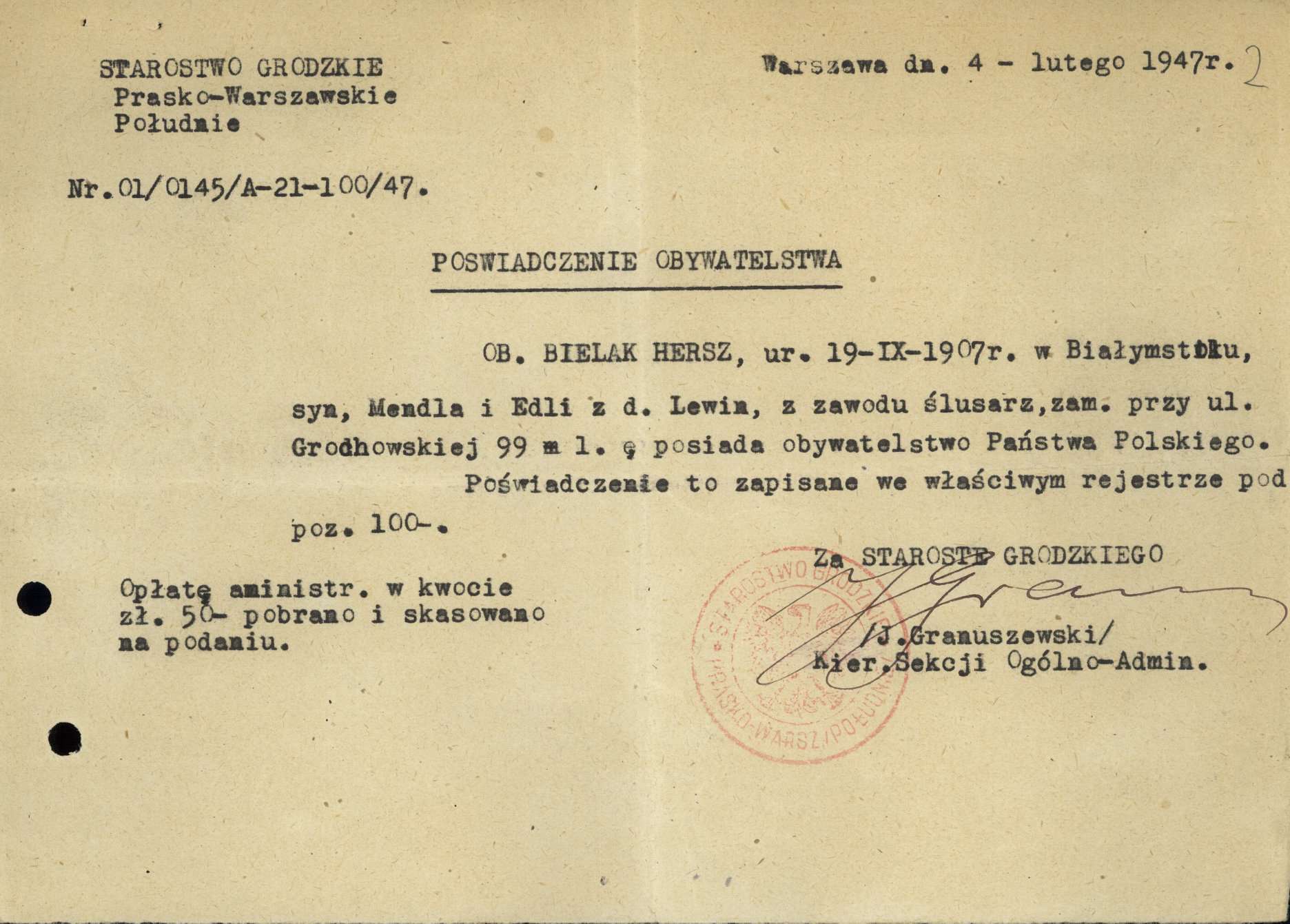

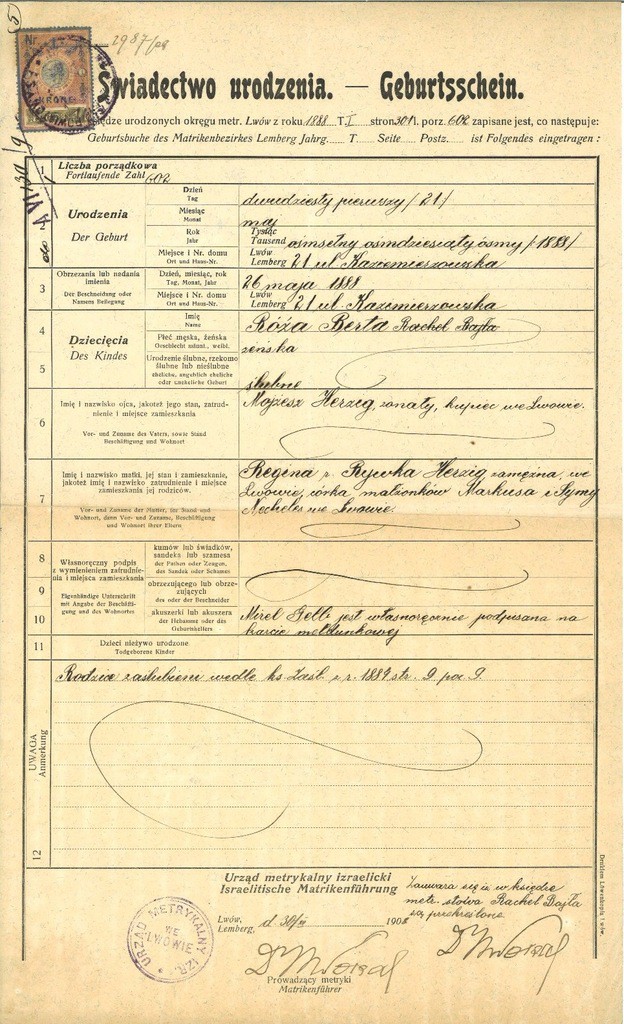

❝ In Poland, Okręg Bożniczy, or Synagogue district, fonds are dedicated entirely to Jewish vital records. They were held separately because, up to 1946, the registration of vital records in Poland was held entirely by church authorities. Therefore, those not under the Catholic, Orthodox or Lutheran churches should have their own registration district. This was handled by the rabbinic authorities. All in all, those records are more scattered than the Christian ones which sometimes presents a challenge for us.

Still, Jewish records can be traced. They are very well digitised and indexed because Jewish genealogists are very hardworking people who make a lot of indexes available online. For example, those looking to claim their Polish citizenship through Jewish ancestry can use Jewish Records Indexing. Their records are mostly dedicated to the nineteenth century. However, they also have records for the first half of the twentieth century. So I would encourage people to use that to trace where the desired record is held and then we can get a certified record from the archive or the registry without any issues.❞

Can you talk a little more about the documentation kept and made available by the Arolsen Archives at the International Center on Nazi Persecution?

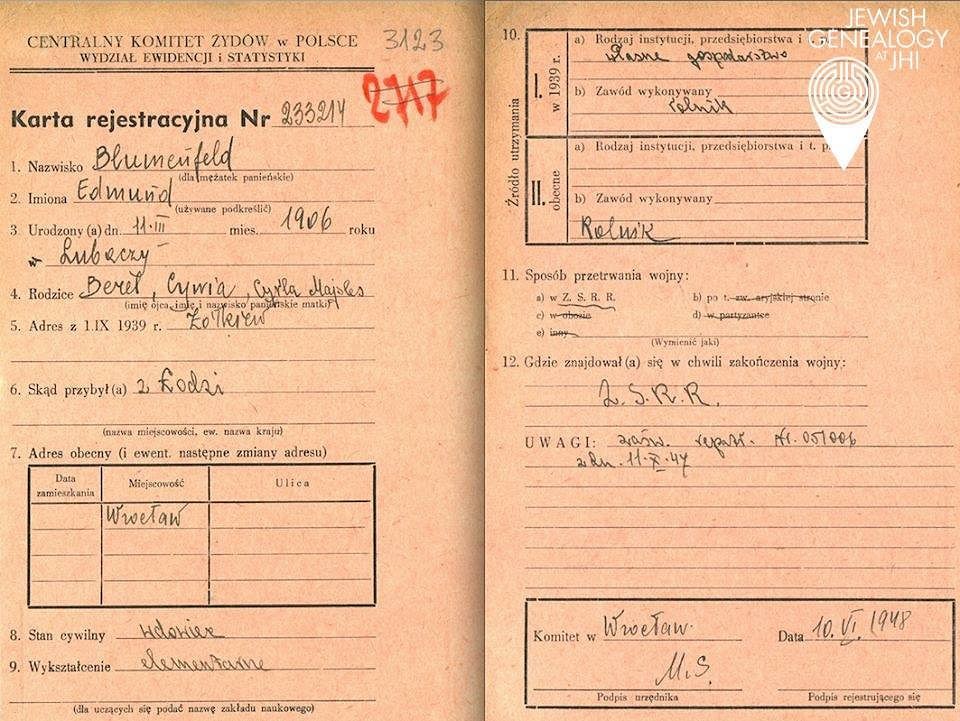

❝ It’s generally recommended to use the Arolsen Archives if your family history involves the Second World War – concentration camps or forced labour in Germany, Austria and Italy. The Arolsen Archives also has information about displaced persons at the end of the Second World War. You can search the online archive. Just put your ancestor’s name and surname and birth date, if you know it, as this will filter out those results which may be misleading. Then you have registration cards because those people applied either for compensation or for emigration to the United States, Australia or any other Commonwealth countries.

Search results also throw up a lot of personal data – for instance, where people lived in Poland as of 1938. You will also see your main ancestor’s parents’ names, creed, occupation and also medical results because they were examined to determine whether they were sick or not. There’s also information pertaining to whether they could work in their new country of choice.❞

On an emotional level, how different is the journey to Polish citizenship by Jewish descent different to the journey non-Jews make? Given that Jews’ experience of living in Poland in the past was not that positive, is the process of applying for citizenship for today’s generations of Polish-Jews more about acceptance of the past and reconciliation than it is getting a passport and being able to live and study in Europe?

❝ In most cases, it involves this deep personal connection and coming to terms with what happened in the past.

On a Polish radio station just yesterday, I discussed the story of the Israeli author, Chava Nissimov. Chava was born in Warsaw in 1939. Her father was killed and mother went missing early on in the war. So Chava was an orphan that was taken care of by a Polish family in Siedlce. Just after the war she left for Israel. She wanted to reconnect with her homeland. So, aided by her exemplary Polish language skills, she came to Poland and applied for citizenship. She was successful, even though documents were thin on the ground because Warsaw was destroyed in 1944.

Fortunately, Chava’s attorney managed to gather a number of documents with our help – the help of Your Roots in Poland. So all turned out well in the end. Chava says that she’s like a phoenix – that she was reborn as a result of getting her Certificate of confirmation of Polish Citizenship. She’s proud that she survived all those hardships and is proud to be Polish and Israeli at the same time.❞

Do you find yourself getting emotionally involved in some of the cases you handle or do you try to treat cooperation as a purely “transactional” matter?

❝ Well, a big advantage of cases such as the one with Chava is that we participate in our clients’ personal histories. We do become very involved in such stories on an emotional level.

Sometimes, I can tell that a Jewish family endured terrible hardships in the past. At the same time, it may happen that the Government adopts an overly bureaucratic stance, making unnecessary demands with regards to the acquisition of certain documents. I might then argue that such and such document is not available. Moreover, the Government might argue that the ancestor held a public office and it’s plain to see that it was a job in a school or they were a doctor or doing a job related to the railways. So I can see that despite all those hardships, the ancestor still made something of himself or herself. However, because they got a better job and learned the local language, the law punishes them, and their descendants, due to the interpretation of what a public office was in Poland. If the ancestor went to work in the mines, for instance, it wouldn’t be a problem as it was not treated as a public office.

When it comes to the cases I’ve personally dealt with, what I’ve just described does worry me because I see that the law and also government officials are doing a huge injustice to these families. I feel the same when families have to wait a very long time for the end result. On the other hand, I do realise that the clerks in the provincial office are so overwhelmed by the number of applications.

I’ve also had clients that were very ill. I knew that they couldn’t wait so long for the end result. This was also a cause of personal emotional pain for me because I couldn’t deliver the result they wanted. Such clients probably didn’t treat the process of getting their Polish citizenship confirmed as a privilege. They perhaps just wanted to end a chapter as they were terminally ill.❞

Useful documentation for acquiring Polish citizenship through Jewish ancestry

Polish Citizenship by Descent FAQ Guide

Got any questions? Perhaps Michał has answered them in this extremely thorough FAQ guide on claiming Polish citizenship by descent:

Claiming Polish Citizenship by Descent – Complete FAQ Guide