This interview with Polish Citizenship Specialist, Michał Petrus, on the topic of Polish citizenship for British citizens of Polish descent follows on nicely from our recent discussions about the range of documents which prove one’s Polish citizenship through ancestry and claiming Polish citizenship through Jewish ancestry. Both interviews I’ve already done with Michał are a fascinating read from both a legal and historical perspective.

Michał is a genealogy enthusiast who’s been handling cases connected with the confirmation of Polish citizenship by descent since 2019. He represents Your Roots in Poland, a genealogical and citizenship company based in Kraków.

Polish Citizenship for British citizens of Polish Descent – Interview with Michał Petrus

1. As with many British citizens of Polish descent, my grandfather settled down in the UK after the Second World War. I think his case was not unusual in that he fought in the Polish Armed Forces in the West under British command. I had to prove to the Polish authorities that my grandfather never left the Polish Armed Forces by serving in the British Armed Forces. Naturally, I worried a bit at the start because I simply assumed that he joined the British Armed Forces due to his ties with Great Britain. However, is it fair to say that most British applicants for Polish citizenship with a relative who fought in the Polish Armed Forces under British command have a clear run to claim a Polish passport?

In general, I’d say that British citizens of Polish descent are in a comfortable position here. Most of the time, somebody in their family served in the Polish Armed Forces. This enables us to retrieve the relative’s military records from the British Ministry of Defence, or MOD. Unlike the collections that are stored in Poland, the MOD records are in perfect condition as they were not damaged or burned during the war.

The only sticking point would be if the ancestor chose to serve in the British Army directly. For example, after serving in the Polish Air Force, some military personnel were transferred or volunteered to join the Royal Air Force. In this case, we can no longer prove that service in the armed forces of a foreign state only covered the period of the Second World War. To be clear, the Polish legal system established that enrolling in Allied military service in a foreign country during World War Two did not result in the loss of Polish citizenship. However, in accordance with the Polish Citizenship Act of 1920, serving in a foreign army would have resulted in the loss of citizenship.

2. Can you provide a bit more historical background as to how Polish citizens would have come to join another country’s forces during the Second World War in the first place?

Polish soldiers who left the Polish Armed Forces tended to join the British Army mostly owing to the prevailing circumstances at the time. The Sikorski–Mayski agreement determined that the USSR would join the Allied forces. This treaty also stipulated that Polish refugees, Polish prisoners-of-war and forced labourers in the Soviet Union were allowed to form Polish units. They were commanded by Polish personnel but were formally under the command of the British Eighth Army.

Therefore, these Poles who were in the Soviet Union followed a trail from central Asia, through Iran, through Palestine and then to the Italian front. After the Italian campaign was concluded, these Polish soldiers travelled to the United Kingdom. Roughly half of them chose to stay either in the UK or Commonwealth countries, while the other half returned to communist Poland.

Regarding active service in other armies, there are some instances of Poles serving in the Free French Forces and in the United States Army. However, I’d still say that 90 percent of cases relate to service in the British Armed Forces.

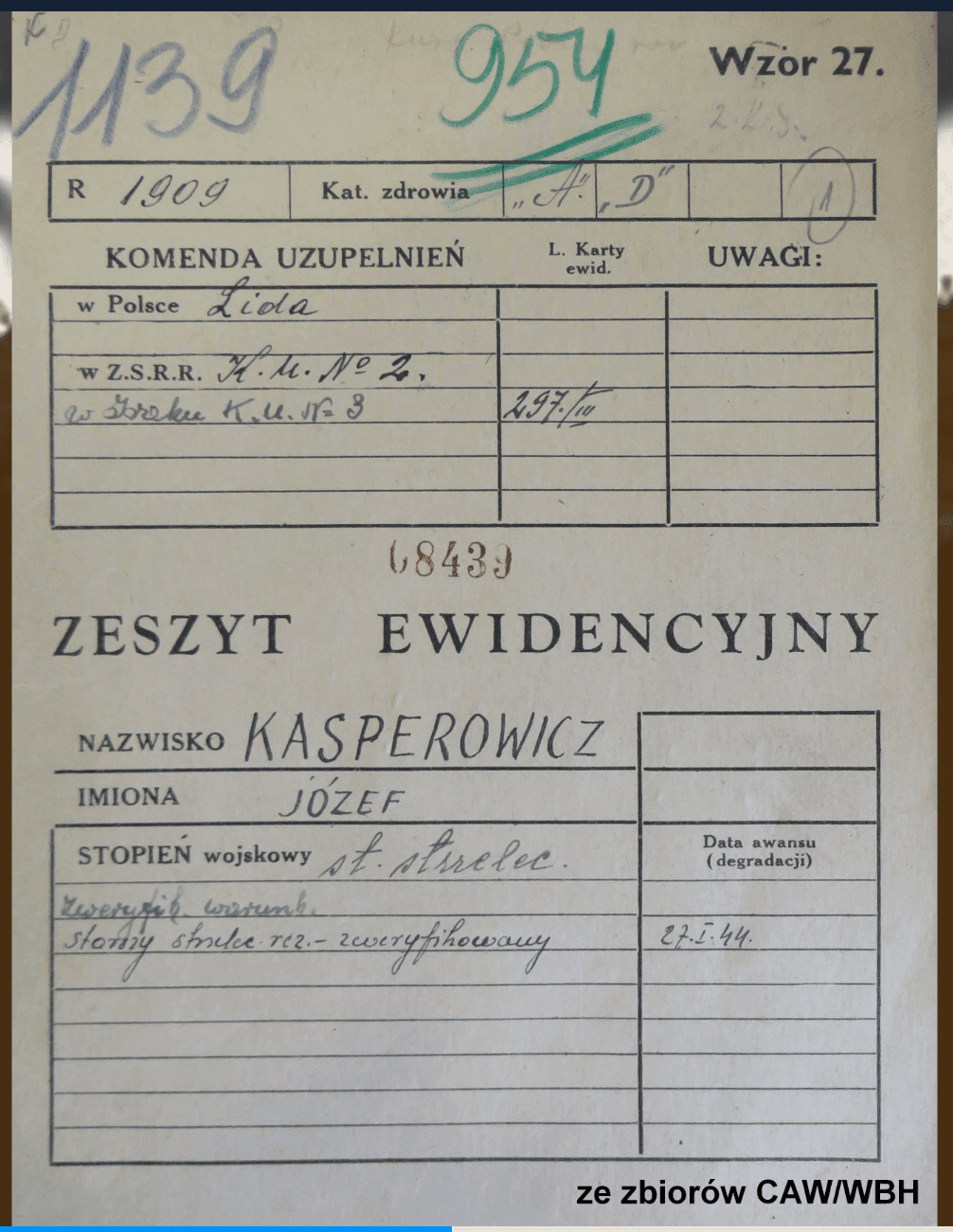

3. I applied to the UK Ministry of Defence (MOD), or more specifically the APC Polish Historical Disclosures section at RAF Northolt, to obtain my grandfather’s Polish book of military records (Zeszyt ewidencyjny). First of all, can you comment on the strength of this document regarding the topic of today’s interview – claiming Polish citizenship for British citizens? Secondly, if one’s relative fought in the Polish Armed Forces under British command, is it almost guaranteed that their records are kept by the MOD in the UK?

If you know for certain that your ancestor fought in the Polish Armed Forces under British command, the MOD will have those records. A relative's book of military records - zeszyt ewidencyjny - confirms Polish citizenship because only Polish citizens themselves can do military service. As I mentioned at the beginning of the interview, military records in the UK were not as heavily impacted as Polish records due to war damages, fires or generally just being missing.

I would also like to mention the Army Cadet Force records. If you have an ancestor that was too young to serve in the army and they were a cadet in the military school under Polish-British command, those files unfortunately went missing. Nobody knows where they are. I’ve contacted the MOD about it several times. The excellent specialist that works at RAF Northolt - Mrs Margaret Goddard - told me that those files are missing as neither the MOD nor the National Archives in Kew have them. The Polish Institute and Sikorski Museum in London does have a few of the records but they’re mostly connected to other files so we shouldn’t assume that the cadet files are in the Sikorski Polish Institute.

Having said all that, if the ancestor served in the army or the ancestor or reached adulthood when the Polish Resettlement Corps* was established (the next unit after the Second Polish Corps** was disbanded), then the records would be held by the MOD.

* What was the Polish Resettlement Corps?

The Polish Resettlement Corps (PRC) was an organisation formed by the British Government and the Polish government-in-exile in 1946. It was mainly run by the British Army. The PRC functioned as a holding unit for members of the Polish Armed Forces who had been serving with the British Armed Forces and did not wish to return to a Communist Poland after the Second World War had ended. It was designed to ease their transition from military into civilian life.

** What was the Polish II Corps?

The Polish II Corps was a major tactical and operational unit of the Polish Armed Forces in the West during the Second World War. The unit was operational between 1943–1947. Commanded by the esteemed Lieutenant General Władysław Anders, the Polish II Corps fought with distinction in the Italian Campaign, in particular at the Battle of Monte Cassino. By the end of 1945, the corps had in excess of 100,000 soldiers.

4. I remember corresponding with Margaret Goddard at the MOD to get my grandfather’s Polish records. A very friendly lady indeed. So, in your experience, the APC Polish Enquiries team at RAF Northolt is very much on the side of applicants?

Absolutely. Mrs Goddard is a very friendly and lovely person. I completely understand that she’s most overwhelmed with inquiries. They do have quite a backlog but she’s very much on the side of applicants. She accepts various documents just to get an inquiry going. Moreover, due to internal regulations within the MOD, they also lessened the requirements regarding the next of kin.

Perhaps when you or your proxy applied for the records, you still needed to prove that you were a legal next of kin. This was due to heavy data protection laws. These days, however, you just need to prove that the ex-serviceman is deceased. Moreover, the MOD no longer charges 30 British pounds for the Polish Enquiries team to do the search. It’s done free of charge.

5. In June 1947, my grandfather joined the Polish Resettlement Corps. He remained in the Corps until the end of April 1948. The letter from the MOD states that “His nationality at that time was recorded as Polish”. With the Corps disbanding in 1949, are the Polish authorities interested in what happened to members of the Polish Armed Forces in the so-called “grey years” at the end of the 1940s before the 1951 Polish Citizenship Act? I ask because I’m not sure what my grandfather exactly got up to after 1949.

Apart from the possibility that an ancestor may have joined the RAF or other direct units of the British Armed Forces, we also need to check whether the ancestor held public office or not in the UK or any other Commonwealth country.

Unfortunately, "Public Office" is a very broad term. The Polish Government basically interprets it as the carrying out of any public service in the public sector. For example, one may have been a medical professional, a teacher in a public school, or even a clerk working for British Railways which was formed on January 1, 1948. The MOD papers also state which civic industry the ancestor transferred to.

If the ancestor was having a hard time and was not able to learn English, they may have been forced to accept lower-paid jobs. For instance, they may have become a coal miner or factory worker. In such situations, descendants of those employed in the mines and factories are, believe it or not, the fortunate ones.

Conversely, if the ancestor was willing to learn the language and attend university to get a higher-paid job, it’s very often an unfortunate situation when it comes to the matter of claiming Polish citizenship for British citizens of Polish descent. For instance, the ancestor may have studied law and became a lawyer. In such cases, we cannot proceed. Holding public office outside of Poland had no impact on citizenship only after 1951. Before 1951, it was incriminating.

Frankly, we strive to avoid talking about the situation if we can. If the issue of public office does not appear in the ancestor’s naturalisation document, MOD file or marriage or birth records, as one’s employment was recorded in such vital records in the UK at the time, then we simply don’t discuss it.

6. The main stumbling block in my application for Polish citizenship was getting a document stating that my grandfather did not acquire British citizenship. This is called a “Letter of no evidence”, and can be obtained from the National Archives in Kew.

In your experience, what are the typical bureaucratic roadblocks British people applying for Polish citizenship might stumble across?

I agree that the early days of those letters may have made applicants for Polish citizenship panic. Nowadays, everyone in the relevant department in the National Archives seems to have pulled their socks up. I haven’t received a Letter of no evidence that’s wrongly formatted in a while.

In general, it’s very rare that the naturalisation of an ancestor derails an application. Given those family histories that we’ve already discussed - the trail from the Soviet Union, through Iran, Palestine and Italy - the ancestor was born way after 1901* in the majority of cases. Even if the naturalisation certificate states that he/she renounced any previous allegiances to the Polish state, that person would still be under the Polish military draft regulations due to their age. At the time, the period of being obliged to perform military service was 50 or even 60 years old depending on the applicable law**.

So, these military draft regulations act as a buffer against naturalisation. Even if your ancestor naturalised before 1951, there is still a great chance, especially if it’s a male ancestor in question, that you will be eligible to apply for Polish citizenship.

Another stumbling block which might get in the way of claiming Polish citizenship for British citizens of Polish descent is name changes. Unfortunately, the post-war period Polish-sounding surnames were an obstacle to a career or in a public school. Therefore, a lot of Polish people changed their surnames to those which sounded more British.

In both the UK and the USA, changing one’s name is not such a formal process as it is in Poland - both back then and nowadays. Therefore, we strive to secure a deed poll confirming the ancestor changed their first name or surname. When I discuss this with my clients, they typically respond that they cannot secure this document as it’s disappeared or they don’t have the original. Perhaps they don't know which notary or lawyer oversaw the deed poll. In such cases, we have to try to secure the full naturalisation papers. These should contain evidence of the name change. Or, perhaps applicants may have access to any other document which shows both names at the same time, or it might show the name change or the aliases. Anything which proves that this is the same person.

If we prove that the ancestor with the Polish-sounding surname served in the Polish Army and had Polish citizenship, it’s still of no use if we cannot show that this is the same person that appears in your birth certificate or in your father’s or mother’s birth certificates.

* Why is the year 1901 so significant when it comes to claiming Polish citizenship by descent?

If somebody was born in 1901, he was eligible for the military draft until 1951. It was in 1951 that Polish citizenship law was amended and naturalisation, holding public office and military service in a foreign army were no longer penalised.

If somebody was born before 1901, and naturalised before 1951, he would have lost his citizenship in 1950, just a year before Polish citizenship law was updated.

** At what ages were Polish men conscripted into the Armed Forces throughout the twentieth century?

Between 1924-1938, the age for compulsory military service was 50. From 1938-1950, it was 60 years old. Then, from 1950, the age was 50 again.

7. Can you talk about some of the other UK-Specific Types Of Polish Citizenship Documents you demand from your clients to help settle applications and matters regarding Polish citizenship for British citizens of Polish descent?

As we’ve already discussed, the documents we require are mostly military records from the MOD. Most of the people that followed the trail from the Soviet Union and ended up in the Second Polish Corps were from Kresy*. For Lithuania and western Ukraine, it is still possible to secure Polish evidence for ancestors from the pre-war period, even going a generation back.

For Belarus and other parts of Ukraine, it might be more tricky. What we can do is to query other institutions that operate from a Polish-British perspective. I’ve already mentioned the Polish Sikorski Institute in London. Such institutes have great collections, for example, from the Government of the Republic of Poland in exile as well as some passport collections and passport questionnaires. The Sikorski Institute does voluntary work so you have to embrace patience with them as it may take them several months to reply. The queries are fairly costly but they are worth it most of the time.

Even recently, I was in touch with a former client based in Australia that had family in the UK before they travelled to Australia to settle there. The client shared a great personal questionnaire showing citizenship, all family connections and pre-war domiciles.

If you know that your ancestor joined the Polish Underground Resistance Movement before moving to the UK, there are quite a few excellent institutions to assist you here. For instance, there is the Home Army Museum [Muzeum Armii Krajowa] in Kraków. The museum and its collections preserve the memory of both the Home Army and the Polish Underground State. There’s also The Polish Underground Movement Study Trust (PUMST), which was founded in London in 1947.

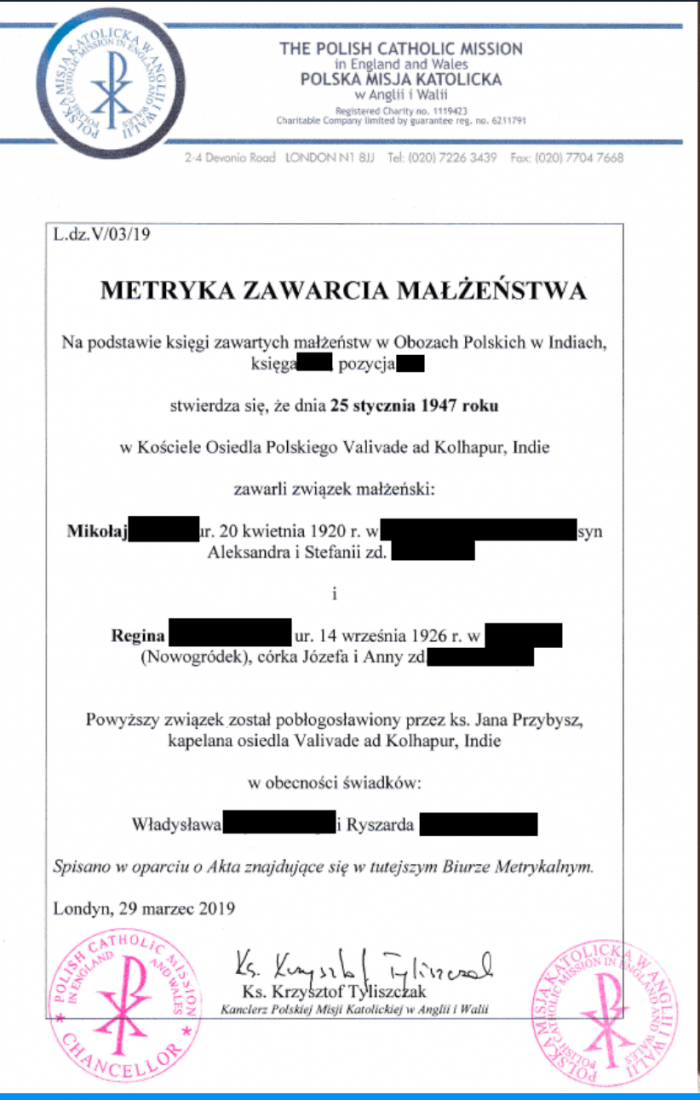

If you fail to secure any administrative or military documents, we can pursue other documents. These include refugee lists and vital records issued by the Polish Catholic Mission for England and Wales. The Mission still operates in the UK and it has an archive from which you can retrieve vital records. In fact, these records were not always registered with the British authorities. Therefore, if you cannot locate vital records in the General Registry Office, it might be the case that the Polish Catholic Mission for England and Wales has them.

Refugee files from the Valivade Polish Camp in India and the refugee camp in Tanganyika, now Tanzania, can be retrieved in Poland. Of course, there were a lot of resettlement camps in former German east-African colonies.

Documents concerning orphans and civil refugees that did not join the Anders’ Army or Polish Second Corps are based in Warsaw. The name of the archive is the Central Archives of Modern Records.

* What does the term Kresy refer to?

The Polish word Kresy translates as ‘Borderlands’. An alternative name for this term that was coined for the eastern part of the Second Polish Republic established after World War I is Kresy Wschodnie – the Eastern Borderlands. The region was historically situated in the eastern Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth. Nevertheless, during the existence of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth, Kresy only referred to the borderlands of the Kingdom of Poland as opposed to the Grand Duchy of Lithuania

Administratively, the territory of the Eastern Borderlands comprised Lwów, Nowogródek, Polesie, Stanisławów, Tarnopol, Wilno, Wołyń, and Białystok voivodeships (provinces). Today, all these regions are within the borders of present-day Western Ukraine, Western Belarus, and south-eastern Lithuania. Of course, the major cities of Lviv, Vilnius, and Grodno are no longer in Poland.

Final thoughts

The topic of Polish citizenship for British citizens of Polish descent is one that is close to my heart as I’ve been through the process myself.

Based on this interview and previous interviews I’ve done with Mr Petrus, it’s clear that the most astute Polish citizenship specialists (I believe Mr Petrus to be one) will most likely come up trumps even if YOU believe that your ancestor’s vital and administrative records are untraceable.

Polish Citizenship by Descent FAQ Guide

Got any questions? Perhaps Michał has answered them in this extremely thorough FAQ guide on claiming Polish citizenship by descent:

Claiming Polish Citizenship by Descent – Complete FAQ Guide